Simon Roberts

April 30th, 2025

Musical Ephemera

Concert posters evolved from marketing tools to collectible art, preserving music history and inspiring a thriving creative collector scene.

Music elicits feelings, sparks ideas, connects, and sometimes divides us. It contributes to our self-identity; it holds a primal, embedded place in our human experience. Visual art is a way to represent that experience, so it’s no surprise that the artifacts of the music industry become treasured items.

In April 2022, a 1966 Beatles “Shea Stadium” poster sold for a hefty $275,000 at a collector auction. On the same day, a 1966 Grateful Dead “Skeleton & Roses” sold for $137,500. This was not the original sheet music written by The Beatles — granted, it’s been long-known that none of The Beatles members could read or write music — nor the guitar played by Jerry Garcia at the Fillmore.

The Beatles “Shea Stadium” promotional poster is just that — a picture of the band with concert information. More of a billboard than art. The more interesting and artistic of the two pieces auctioned that April day is the Grateful Dead “Skeleton & Roses” poster, which was created through the collaboration of Stanley “Mouse” Miller and Alton Kelley, two of the godfathers of the gig poster industry.

These two pieces, produced in the same year, represent a clear divergence between a marketing department-driven band poster and a unique artistic expression. The latter occupies the transitional space between consumer art and collectible fine art.

“There may be a nostalgia at play, where people collect shows they attend and get to hang some history on their walls,” San Francisco Bay area rock poster artist Zoltron says of the collector market for gig posters. “Then there’s a thriving aftermarket and entire communities devoted to collecting and buying and selling and trading, where speculators find value knowing supply is always going to be outweighed by demand.”

These are the ephemeral artifacts of the music industry, the impermanent debris of music promotion; faded concert posters pinned to teenagers’ bedroom walls, bleached by the sun, torn and frayed at the edges.

In the last 25 years, concert or “gig” posters, driven by the musicians they are associated with, rarity, historical significance, and their artistic qualities, have become recognized as extremely collectible artwork.

Generations of Illustrations

Before the advent of concert posters can be understood, a quick stroll through printmaking history is needed. For the sake of brevity and avoiding a less than captivating dissertation on the invention and evolution of lithography, skip ahead to the turn of the century when printing technology evolved, and color exploded onto posters.

The early 1920s saw the art deco movement influence the content, color, and style of posters. The jazz movement of the 20s and 30s adopted art, streamlined typography, and introduced the modern aesthetic of the period for their concert posters.

Oddly enough, the early rock and roll concert promoters of the 1950s moved away from artistic expression and favored using the “boxing-style poster,” which featured simple photos of musicians and bold typography to convey important information about the upcoming concert.

The psychedelic rock era of the 1960s marked a dramatic shift in posters. Artists were commissioned to create highly conceptual, vibrant, and surreal artwork to match the musical acts they represented. Artists like Rick Griffin, Wes Wilson, Victor Moscoso, Miller, and Kelley are credited with creating the psychedelic style featured in posters for bands such as the Grateful Dead, Santana, Jimi Hendrix, The Who, Cream, and The Beatles.

“The gateway art for me was [the] discarded underground comix from the San Francisco 60s scene,” Zoltron explains. “Those fearless pioneers like Gilbert Shelton and Dave Sheridan’s Freak Brothers, Zap Comix, Victor Moscoso and Rick Griffin, S. Clay Wilson’s checkered demon, and Crumb’s Mr. Natural. All those fucked up 60s artists who destroyed my adolescent mind and pointed me toward a lifelong love of the twisted and absurd.”

The psychedelic era of concert posters has become the most well-known and vigorously collected genre. Bands of the period outgrew clubs and smaller venues like the Fillmore and shifted to stadiums, and the need for promotional posters waned. Its resurrection was found in the 70s and 80s in the anger and angst of punk rock shows — no self-respecting punk calls a punk show a “concert” or “gig.”

Inspired by a lack of industry support, the punk rock scene embraced the DIY minimalism aesthetic. These homemade punk rock posters — technically flyers or mini posters — were spartan works featuring handwritten or rough typography, confrontational imagery, and social commentary. Their handmade aggressive style reveals the insurgent discord felt by the punk rock youth. The famed “ransom-note” style posters were popularized during these early years with lettering and imagery cut out and pasted in a collage.

As punk rock grew in popularity, it found a natural alliance with artists in the underground comix scene. Both groups featured a DIY ethos, anti-establishment sentiments, progressive social commentary, and a couldn’t-care-less attitude about whom they might offend.

The 1980s also saw the meteoric rise of hip-hop, which shared the same DIY musical and artistic spirit as punk. Graffiti or using the gentrified nomenclature “street art” served as a visual language for the hip-hop scene.

Ken Taylor creates bold, intricately designed concert posters, and has worked with several big-name bands such as Pearl Jam, Pixies, Metallica, and Phish. The Western Australian artist found inspiration in hip-hop music and the graffiti art scene during the birth of his career. “The confluence of art school, love of music, love of graffiti, and the fact that my friends and family were in bands were the basis for my start in the gig poster industry,” Taylor recalls. “I was the go-to person in my group of friends who would make flyers and posters, largely for free or little expense to the bands.”

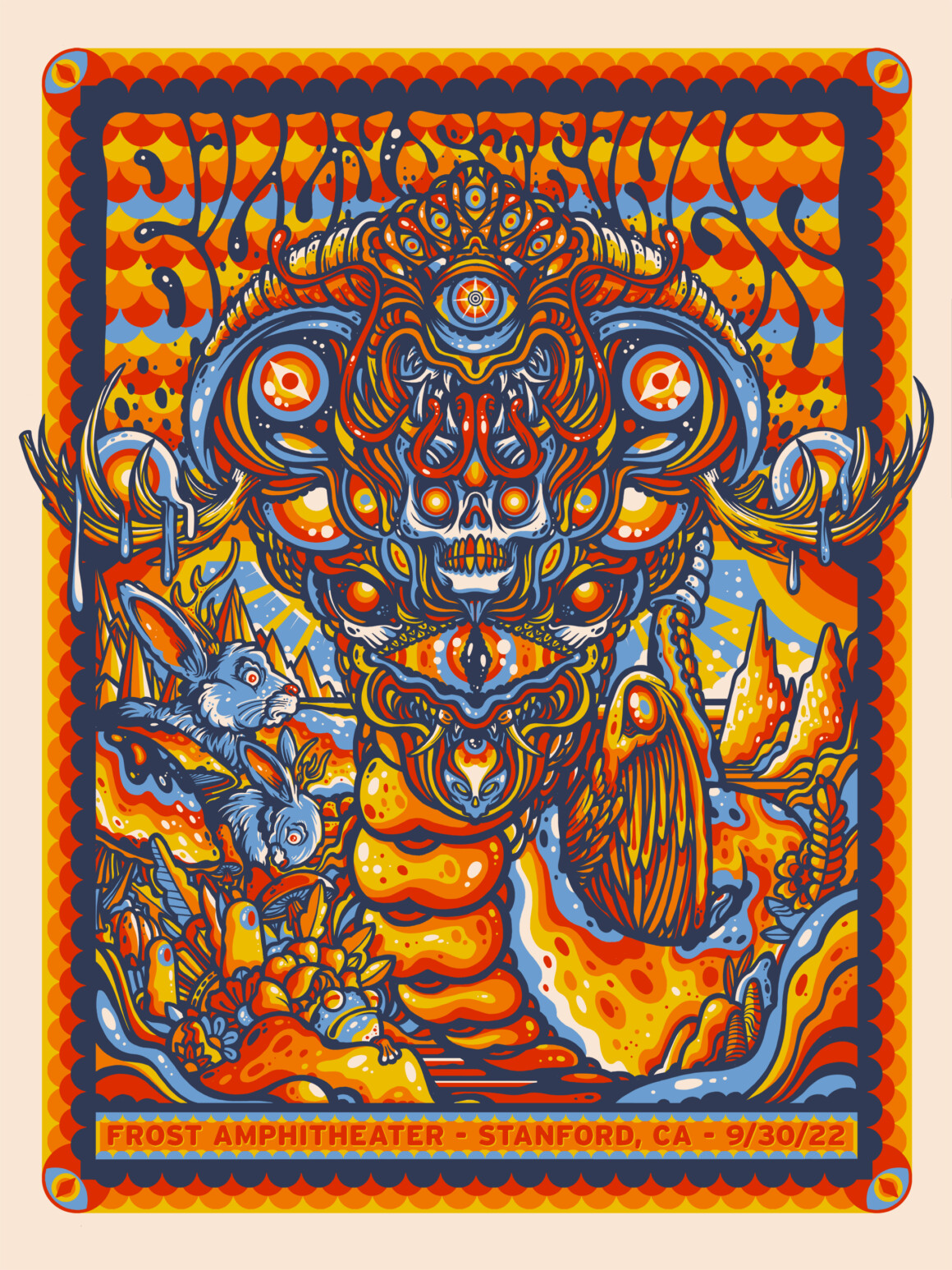

As punk, pop, hip-hop, metal, and alternative rock reigned in the 90s, artists like Frank Kozik gained fame for his often satirical and grotesque posters with direct nods to his underground comix heritage. Bands like the Melvins, Sonic Youth, Nirvana, Stone Temple Pilots, Beastie Boys, Green Day, Dinosaur Jr., and Butthole Surfers had posters created by Kozik. Other artists like Chuck Sperry created posters for bands like Pearl Jam, Smashing Pumpkins, U2, Widespread Panic, Rancid, and The Black Keys in a variety of styles and concepts that continued to push the acceptance of concert posters as modern art.

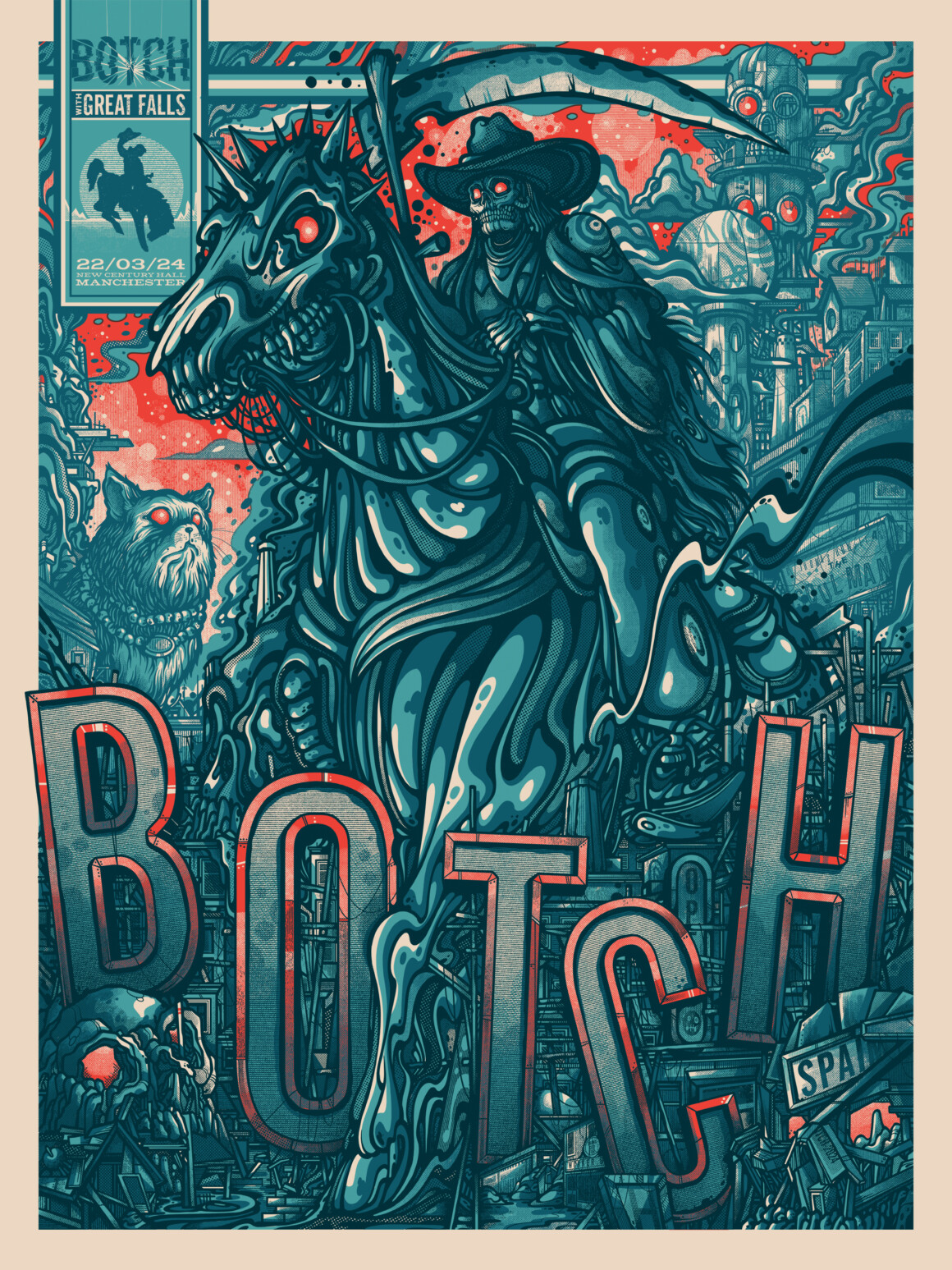

As a fledgling artist in the early 2000s, Drew Millward, a poster artist from the Aire Valley in England, drew inspiration from the post-industrial punk scene in working-class towns. “It was purely through necessity that I got into gig posters,” he says, explaining, “During university, I was running a fanzine with friends, which led to putting on gigs. A friend of mine and I started taking turns making posters for the shows. Word got out in our music scene, and I began to make posters for other gigs and other bands. The money was not good, but it was enough for me to quit a job I hated.”

The 80s and 90s were an intense period of creativity that served as an incubation for some of the most important and prolific artists in the creative space today. The poster industry flourished during this chapter, and although the technology had been available for years, the adoption of silkscreen printing allowed for even more intricate and colorful works of art. Posters echoed everything from tattoo flash art to underground comics and art school vibe modernism.

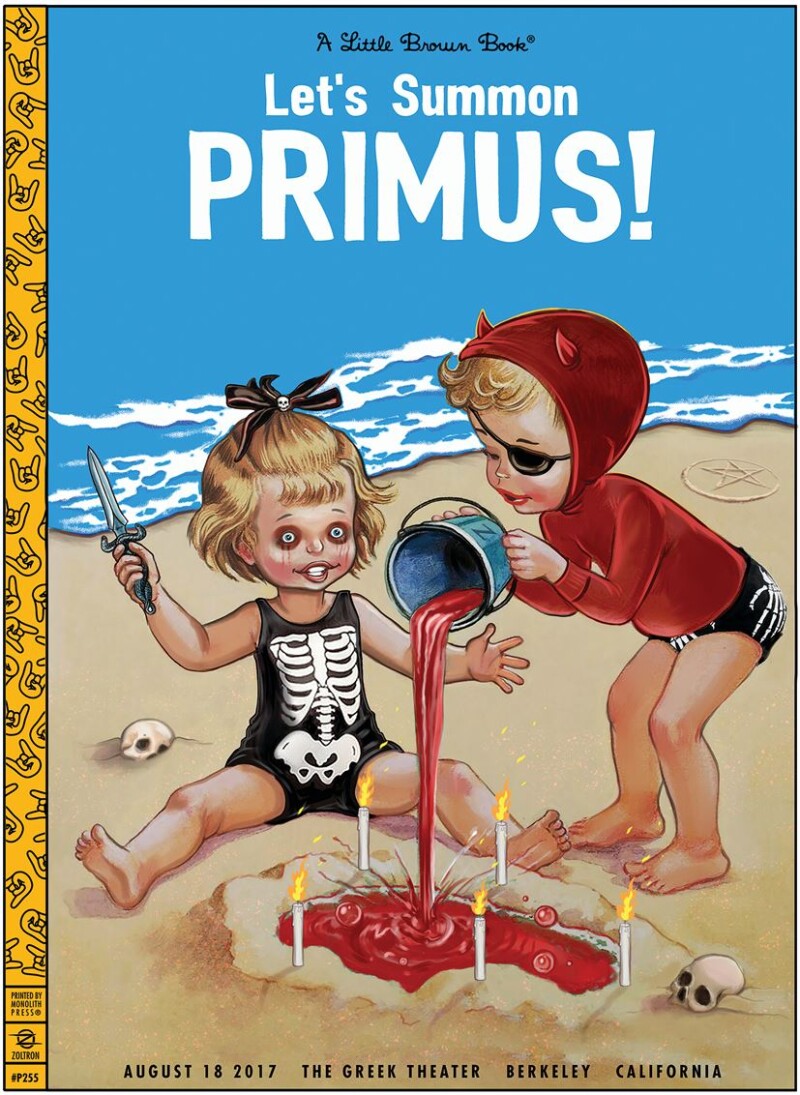

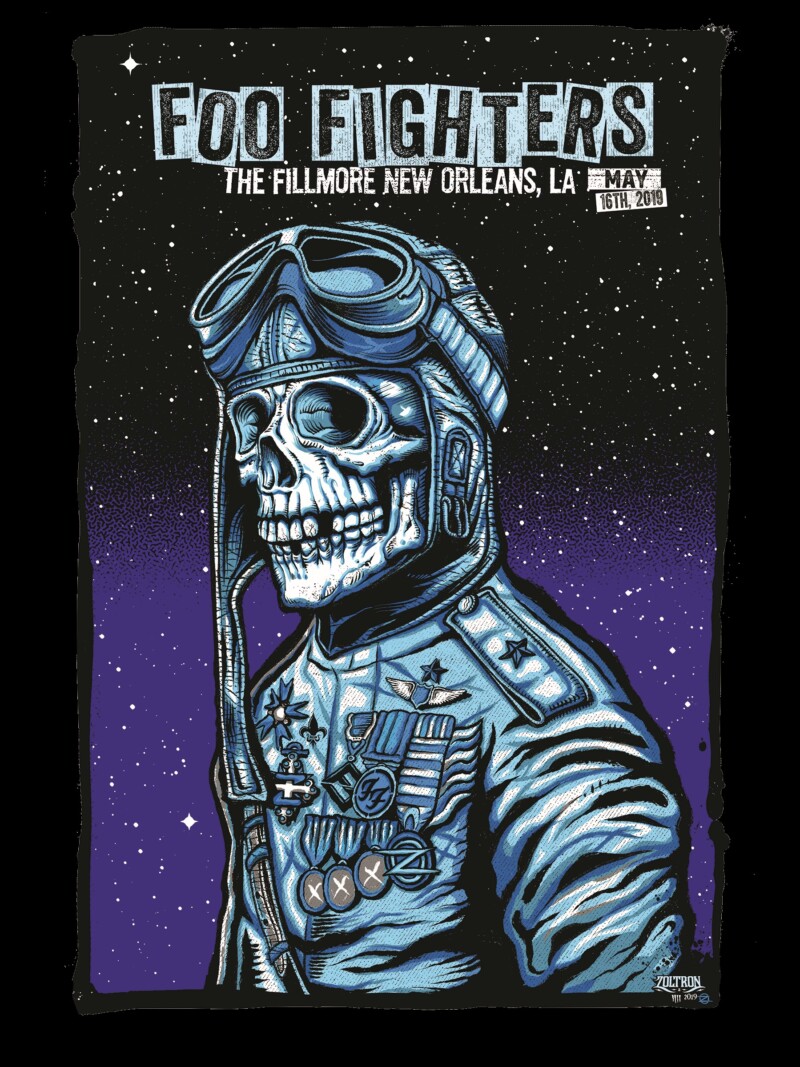

Zoltron’s portfolio is brimming with heavy-hitting rock bands such as Primus, Alice in Chains, The Black Keys, Foo Fighters, and Nine Inch Nails. “The good news is that the silkscreen collector scene is alive and well,” Zoltron says. “There’s really been a renaissance for hand-printed editions; maybe it’s a resurgence of tactile art in a digital age. Something about holding a print that was created the same way it has been for a thousand years, smelling the ink, running your fingers over the embossed surface of a print, knowing that the editions won’t be reprinted.”

With the invention of the internet and digital media came another change in the poster game: direct sales to customers and limited-edition prints. Many artists also create specialized limited-edition versions of a particular event that go to the collector scene. These are handmade, small-batch pieces that sell for a much higher price than large-run posters sold at events.

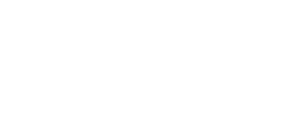

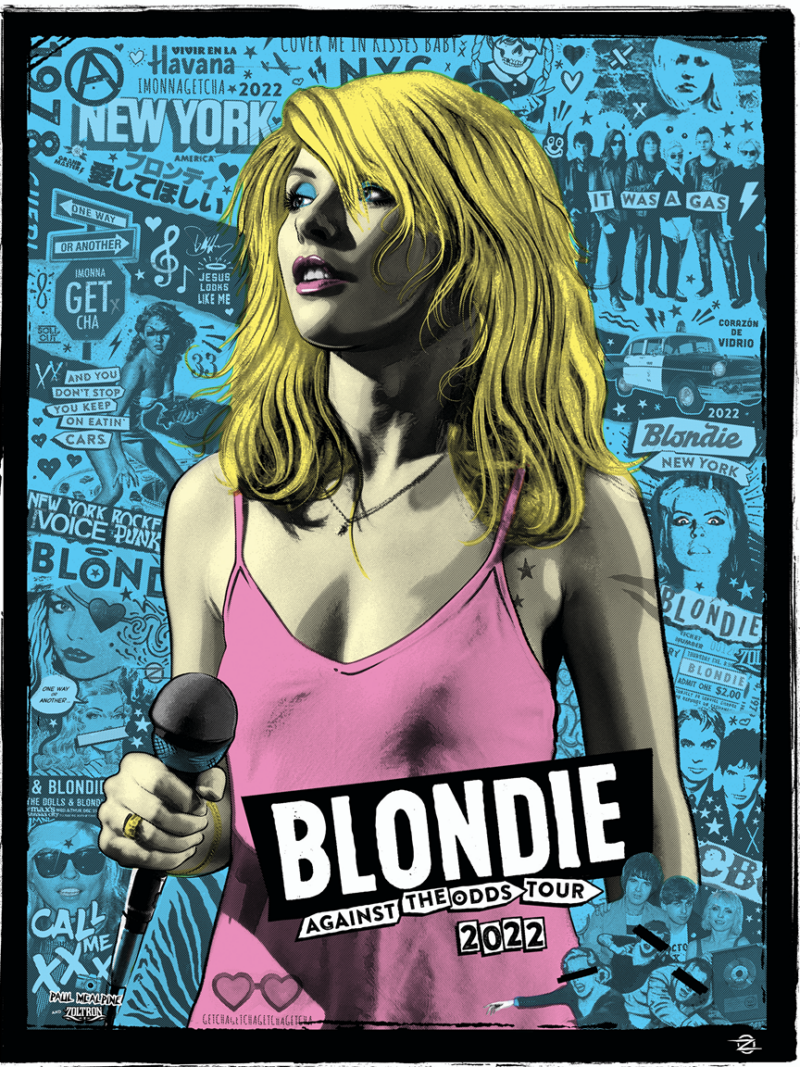

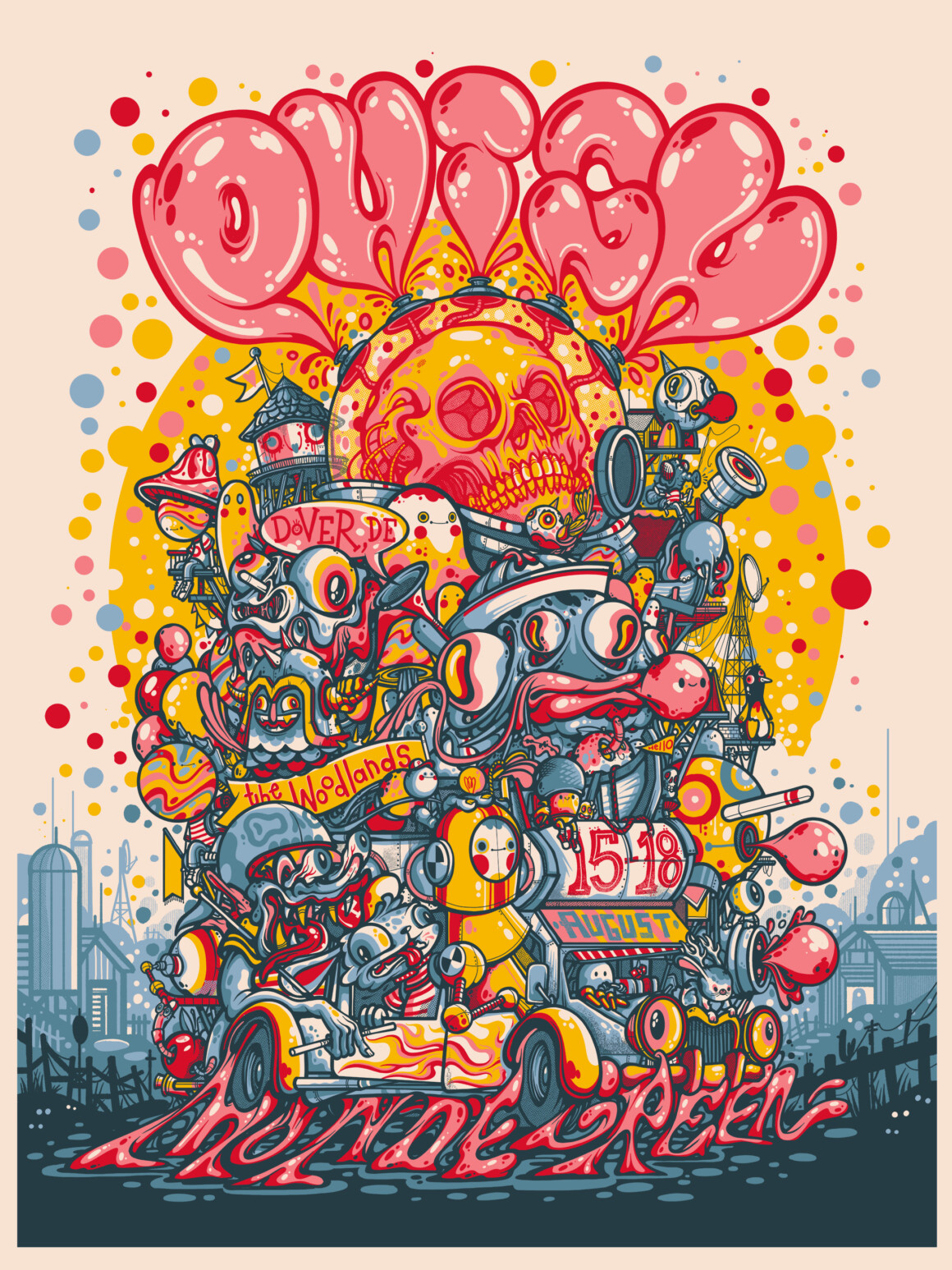

On occasion, concert poster artists are commissioned for special projects. For instance, Zoltron created a “twisted children’s book series for Primus” and is currently making a bronze, life-size Foo Fighters astronaut statue. He jokes that he deserves a good record for his rendition of WEEN’s 30th-anniversary re-release of “Chocolate and Cheese.” “Management had sent me a pre-release of the new album, and because I wanted to kind of tattoo her entire body with song references, I listened to that album like 40 times,” he says. “Every song is referenced, and diehard fans can read her body like a lyric sheet.”

Physical items like posters, album covers, and t-shirts are material representations of our attachment to music. They capture the specific date, time, and place of an emotional experience. These items seldom survive throughout our lives, even though the music and emotions connected to them endure.

Editor's Picks

Two-Wheel Temptations

Explore the best motorcycles and gear for every rider, from adventure touring to superbikes, plus must-have accessories for performance and safety.

A Toast to Craftsmanship

American Metal Whiskey is an iconic spirit born from custom hot rod and motorcycle culture.