Inked Mag Staff

October 5th, 2016

Crazy Philadelphia Eddie

Inked has learned that Crazy Philadelphia Eddie has entered hospice care. We are saddened to hear of the decline of tattoo’s liveliest characters. Below is an interview we published in…

Inked has learned that Crazy Philadelphia Eddie has entered hospice care. We are saddened to hear of the decline of tattoo’s liveliest characters. Below is an interview we published in our September 2012 issue, that was conducted by one of his greatest friends Eric Foemmel.

Edward Funk is known as Crazy Philadelphia Eddie to his friends and the entire tattoo industry. Tattooing since 1952, Funk has not only shaped, influenced, and equipped the tattoo business, he’s also worked with other artists to protect it in New York State’s highest court. And he’s quite the character. In this interview,

Crazy Philadelphia Eddie discusses why he wanted to unite tattoo artists, his fight against the New York City Department of Health’s ban on tattooing, writing his books, and his recent experience on the convention circuit.

INKED: You tattooed for more than 50 years, opened numerous shops, and started the National Tattoo Association. What was it about tattooing that made you want to accomplish all these things?

EDDIE: Well, I think it really had to do with Chinesef ood. [Laughs.] What made me want to accomplish these things? When I’d seen how authorities, people with authority, health departments, and city officials wanted to do away with tattooing, my goal was to protect tattooing, to keep tattooing alive and flourishing, and the way to do this was to unite the tattoo artists. In uniting, we had power. It was money that could be collected from everyone, and you could get lawyers and fight opposing people that wanted to do away with something that has been going on since time began. Tattooing, they say, is one of the first two professions. Prostitution and tattooing—we don’t know which came first, but I like them both.

As you say, tattooing has always been under fire, and it was banned in New York City and throughout much of the East Coast in the 1960s. What was it like fighting the ban in court?

It was a battle that I felt I could not lose. I didn’t feel that I had all the winning components on my side, but I felt, if I lose this, that’s my life. My life was tattooing, so I had to win this battle.

You’ve never done anything except tattoo?

Right.

And you chose your profession at the age of 15?

Yes.

And the guys before you—Brooklyn Blackie, Max Peltz, Jack Redcloud—were they always coming under the same fire from the authorities?

Brooklyn Blackie used to say—he used to get raided when I worked with him—he’d say, “We get raided three or four times a year. You have to expect to be arrested for some minor shit like tattooing a minor every two or three years.” Every two or three years you had to expect this to happen to you. It is part of the profession, part of the trade, and part of being a pirate.

What do you remember about the New York State Supreme Court trial?

I kept saying to myself, “This judge [Justice Jacob Markowitz] is for tattooing. I wouldn’t be surprised if he lifted up his robe and had some tattoos on him” because everything the health department was throwing at us, the judge was saying to our lawyer, “Don’t you object to that?” and the judge appeared to be extremely fair and in favor of saving the tattooing. There was no jury. It was up to the judge. At the very end of the trial, the judge said he has heard enough, he will take everything under advisement, and give us his verdict in a short time. My lawyer said that short time could be months, could be three months, six months, a year. He said, “This is a big case, and he can’t make a decision like that. He’ll have to take that under advisement, and talk it over with other judges and lawyers before he can even make a decision because you can’t make a decision to break the law, and you can’t make a decision that is unfair.” So it would take a lot of advisement before he could make a decision.

How underground was tattooing in New York during this ordeal?

At the time, Coney Island Freddie [one of the case’s plaintiffs] lived and worked in this housing development that was a secured community where you had to come through a little gate. A security guard there would ask you who you were coming to see and phone the people. So Freddie was tattooing inside this little fortress, and therefore, he wasn’t going to get arrested. He would tattoo the people, and if somebody was coming who was not welcome, the security guard would alert Fred by saying, “so-and-so is here to see you.” So Freddie was having a great business inside this little security community. I had already been established in Philadelphia, and when the decision came down [in 1963] that tattooing could be practiced safely in the city of New York, and the health department should get officials to supervise it, and that … it was legal to open … Freddie and I were not interested.

We were happy with what we were doing. A few people did open in New York, and then the health department came back with an appeal to overrule the verdict [in 1964], and they eventually won [in 1966] because there was nobody there to fight.

But if you were living there, you would have fought it?

If I was living in New York, I would have fought it. Yes.

You traveled a lot. It seems that you were always going somewhere. What effect have your travels had on your tattooing?

It improved it. It gave me more knowledge. I traveled through this country and Europe. I traveled into Canada, and I always went to see the tattoo artists wherever I went to learn what I could from them, to learn about tattooing itself, about the rules and regulations, and I just strengthened myself to where I was very knowledgeable—there wasn’t anything that went on in tattooing that I didn’t know about. That is because I traveled and got opinions from north, south, east and west. Yeah.

Through your travels, did you meet a lot of people who later joined the National Tattoo Association?

Yes! In meeting all of these people in my travels, I had their business cards, which I saved. And when I had the idea to start this association, I just wrote to each one of these people and told them my plan, and being that I met them—and I make friends very easily—all of these people I met were glad to sit down and talk with me, and they agreed with what I was trying to do. It would be something that would benefit all of us, and it was very easy to start this national club.

Was the main goal to unite the tattooers, and to have some power so the authorities couldn’t harass you?

Yes, that was the main goal. I’m thinking, if you saved all the cards and wrote everyone, back then there were not many tattoo artists. So there were not a lot of people to contact. It was fairly safe to say, between tattoo shops, it was 300 miles, so there wasn’t that many tattooers—and I got to meet them all. Or if I didn’t meet them, I knew of them, and I got their phone numbers through phone books and other tattooers. I contacted each tattooer and I started this club. I thought I contacted all the tattooers in the world, but I didn’t. I later estimated there were 300 people tattooing on the globe, and if we could have that many in our little association-club, and each one paid their dues, we would have quite a bankroll to fight whatever steamroller came at us.

That was in the 1970s?

Yeah.

And you retired in 1992?

That’s a tough question. I retired so many times, I don’t know which one was the real one.

But you don’t tattoo anymore?

No.

Now you’ve been working on a series of books about your life. What inspired you to write your books?

People. People said to me, “Eddie, you know so much about tattooing, and you lived in such times that don’t exist anymore, that if you don’t write it down and tell everybody, when you’re gone, it will be lost forever.” So I said, “Okay, I can write a book.” I decided I’ll do that; I’ll write a book.

What do you want people to understand or come away with after reading your books?

How things were, how things are, and how things will be. The future does not look good. The past is gone and lost forever. It cannot be brought back. But some of the ways, it would be neat to see them come to life again. And the now is now, and if you don’t do it now, it will never be done. It will be lost, and the future does not look good. And if we don’t bring some of the past back, we’re all doomed.

You’ve been to 25 tattoo conventions in the last year. What do you like about them?

The excitement! Each convention is a little different, each crowd—although there are many people who attend quite a few conventions, conventioneers, I call them—there is always a local group where the convention is held that is different than the last one or the next one. And the excitement of talking to these people, the flair and the enthusiasm that each individual has, spills on to the next and to the next. And it just keeps getting better and better. The excitement of seeing the new styles of tattooing, that will never end because tomorrow is different than yesterday.

How do people receive you at conventions?

The response I am getting is overwhelming to me. The kindness, the love, and the respect I get from these conventions is just—it overwhelms me. I didn’t realize that I had such an influence on so many individual people.

Is there any truth to the rumor that you threw the first tattoo convention in the United States?

No, Dave Yurkew threw the first tattoo convention in Houston, TX. And two years later I did one, forming the National Tattoo Club.

When you threw the convention for the National Tattoo Club, what was the main goal?

To unite everybody, to get everybody together and be a union. The movie industry had their conventions and gave awards to the good actors and to the supporting actors, for the scenery, for the ideas, and I figured that if we could do that for the tattooing, there would be no end, no no limits to where we could go.

Editor's Picks

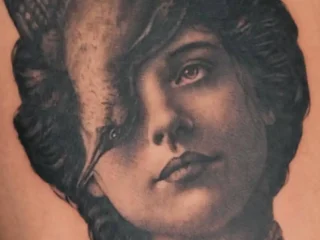

Bridging Classical Art and Modern Tattooing

Esteban Rodriguez brings the discipline of classical fine art to the living canvas of skin, creating hyper-realistic tattoos that merge technical mastery with emotional depth.

Show Your Ink Fashions Brings Custom Style to Tattoo Culture

Show Your Ink Fashions creates custom shirts designed to showcase your tattoos as wearable art, blending fashion with personal expression.

The Ultimate “Superman” Tattoo Roundup: Just in Time for Superman’s Return to Screens

With Superman’s big return to theaters, fans are revisiting some of the most iconic ink inspired by the Man of Steel.