Nia Groce

May 19th, 2025

Reka Nyari – Body Language

Reka Nyari captures powerful portraits of tattooed individuals, blending storytelling, art, and raw human expression through her lens.

They wear their stories on their skin. She tells them through her lens. Helsinki-born and New York-based, photographer Reka Nyari’s journey to capturing the heavily tattooed was as artistically layered as the subjects taking center stage in her works.

“I don’t know why when I was younger I thought ‘art’ was painting,” she says, the adolescent belief leading her to study said subject at the School of Visual Arts in New York. “But I always would take photos as references,” she recalls, explaining that even when she took on modeling stints in Europe and Southeast Asia, despite being sans painting materials, she was ever-inspired to shoot. And did.

“It’s when I discovered that photography is actually an art medium and it’s something that I love to do. It’s so much more collaborative than painting by yourself in your room,” she says. Enter Nyari’s commercial work era in the fashion and beauty space, followed some years later by what now seems to be her sweet spot. “Art photography. Telling my own stories and, instead of selling products and things, creating art,” she explains.

Skin Deep

Creating images and being a storyteller— and shifting narratives alongside them — is a holistic practice for Nyari. It’s part of her draw to tattoos, which, besides being personally fascinated by, she feels weren’t — and still aren’t — represented enough in the fine art world, inspiring her to kick off her “INK STORIES” series circa 2017.

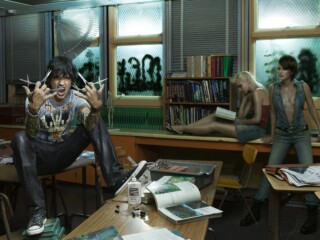

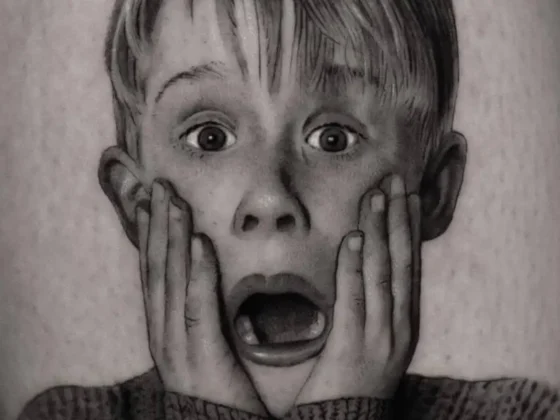

The photographer paints the portrait of a stubborn, lingering taboo in “traditional” art spaces. Her subjects were likened to “criminals.” Visitors stood aghast with “Oh, my God” reactions at the sight of her large-scale portraits, the depiction of these emboldened — and naked — women inconceivable to any authentic art connection.

Seemingly outdated in an age of unabashed self-expression, these notions are ever in style in the “conservative environments” where some of her exhibitions have opened. The discussion is usually expected. Sometimes of her own habit to “instigate.” And always welcome.

“I’m flattered if somebody doesn’t like my work. I think reaction is better than overreaction,” Nyari proclaims. “Also, I think it says a lot, reaction to art, about the person who’s looking at it.” She explains that her Nordic roots, and thus sauna culture, shaped some of her own perceptions. “I was raised with nudity that was non-sexualized a lot.”

Naked Truth

Still, Nyari acknowledges that they are technically “nudes.” And what, if any, responsibility does she feel with capturing individuals in these vulnerable states? “As a woman shooting other women that are in a state of undress, I just lean on that person to give me as much as they want to give,” she says. “My objective is not to shoot them sexy or in an erotic way… so there’s that line of what is that woman comfortable with showing? How do they want to portray themselves? So, depending on their own story, it can be empowering to be sexy and naked and say ‘See me, bro. This is my skin. This is my story.’”

If the reaction, as Nyari notes, says a lot about the person looking at it, what then does the photograph say about the person taking it? Is Nyari herself a tattoo artist? Is her skin, too, her canvas of choice, working her way up to a body suit akin to her subjects?

To the former, no. And maybe more surprisingly on the latter, also no. But neither is off the drawing board, per se. Like any true artist, Nyari respects the art, the process, and, in the case of tattoos, the commitment, which she has now heard countless first-hand stories.

“Apparently the more tattoos you get, the more your body responds and the pain becomes more instead of less. Your immune system starts reacting more,” Nyari explains. One such subject has provided one of the most memorable proof points. “I shot this amazing French woman, and she has three body suits on top of each other,” she says. “She was telling me she was called a ‘true collector.’ It’s such a commitment to the art.”

Besides, if and/or when Nyari is ready to turn her eye for ink onto her own body, it’s go big or not at all. Turns out her teenage desires still linger but have matured. “I wanted to get my first tattoo when I was 14. I designed this massive back piece, and my mom said, ‘Wait until you’re 18, and then I’ll come with you. I’ll pay for it,’” she recalls. “By the time I was 18, I’d changed my mind. Now that I’ve shot so many amazing fully tattooed [people], it’s art,” she adds. “I couldn’t get anything small. It would have to be a full body art piece.”

Best Undressed

Until then, Nyari is “living vicariously” through the inked-up individuals she photographs, “capturing their life stories and giving them a voice.” And continuing to maneuver within, and arguably trailblaze, the photography fine art space of tattooing.

Her network has grown to the point of word-of-mouth hook-ups. “People find me now, also,” she explains of new subjects. And her purview has expanded to community captures in some instances, detailing an upcoming project with “portraiture of actual tribes.”

And now, even high color has seeped into at least one of her typically black-and-white projects, representing a moment to “flip everything upside down” post-COVID. And yes, by the way, she does shoot men too — and always has — so look out for her project featuring “generally masculine themes of tattooing, with something typically feminine” to come soon.

No matter the individual or the tattoo, the draw for Nyari remains the same: art as its own story and the art of telling those stories. Their canvas. Her capture.

“I like scars and imperfections and all these different things on bodies. And tattooing is just another layer of telling a story on top of it,” Nyari says. “It’s almost like art on top of art, you know?”

Editor's Picks

The Ink That Heals: Inside Veteran Ink’s Mission to Help Heroes Through Art

For many veterans, tattoos are more than body art—they’re a way to process pain, honor service, and remember the stories that shaped them.