Elaine Maguire O’Connor

February 12th, 2025

Beyond Skin Deep

From MGK to Miley Cyrus, tattoo trends spark cultural appropriation debates. Learn why research and respect are crucial before getting inked.

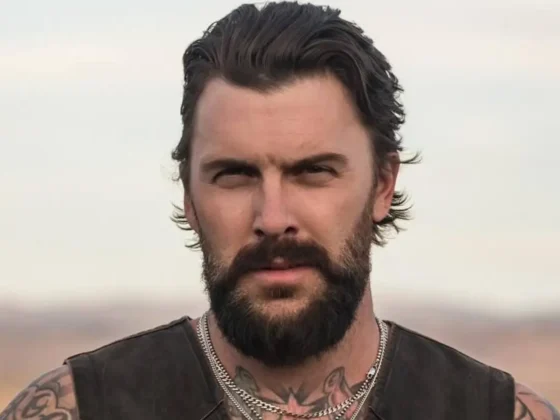

When Machine Gun Kelly debuted his blackout tattoo, the internet was quick to react. Accusations of cultural appropriation and comparisons with blackface sprang up on Instagram comments. Others defended his tattoo as being unconnected to race and, instead, a method of covering up old, unwanted ink without going through the pain of laser removal.

MGK wasn’t the first celebrity at the center of an internet storm for his tattoo choice. Miley Cyrus faced a similar backlash when she first unveiled the dream catcher tattoo on her ribcage, a symbol originating from the Ojibwe tribe which Cyrus has no apparent connection.

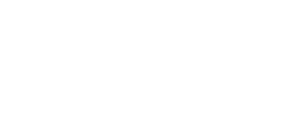

Like fashion, tattoo trends fall in and out of style. The 80s saw the rise of tribal tattoos, with Māori and Celtic designs adorning the arms of many. The 90s gave birth to the obligatory Chinese symbol tattoos and the 2000s witnessed a flurry of sugar skulls and Day of the Dead-inspired ink. But these seemingly innocuous tattoos are more than just cool designs or reminders of the fashions of our youth.

For the Māori tribe, tattoos are specific symbolic representations of sacred relationships with a much deeper meaning. Many consider Westerners who sport these tattoos disrespectful of their culture and the tattoo’s symbolism within Māori society. More recently, a debate over whether sugar skull tattoos are culturally insensitive when inked onto those who don’t properly celebrate or even understand the importance of Día de los Muertos has played out on blogs and social media.

Cultural appropriation, the adoption of customs, practices, or ideas of one society by a member of another, is not a new issue to the tattoo industry, nor is it unique. The phrase first appeared in print in 1945 in an essay by Arthur E. Christy, who was writing about “European cultural appropriation from the Orient,” but the practice of dominant cultures adopting and exploiting the culture of marginalized ones can be traced back hundreds if not thousands of years. More recently, the problem gained prominence in the worlds of music and fashion where the matter of large companies profiteering from cultural traditions is rife. Multiple luxury fashion brands including Gucci and Dolce & Gabbana have been forced to apologize and pull products and advertising campaigns over accusations of appropriation. But, given their permanence, it’s not easy to backtrack on ill-advised tattoos.

A lack of understanding around boundaries between participating in culture and appropriating has resulted in heated debates regarding what some consider innocuous designs or gestures of appreciation. A common argument, particularly in the U.S., is that humankind is a melting pot of multiple cultures that have been assimilated and melded together and that, as a result, no person or group can lay claim to a particular symbol or image. But this argument ignores the power dynamics that play out across society, the effects of colonialism, and the commodification of cultures affected.

Mona Maruyama, a tattoo artist specializing in Hajichi —a traditional style of ink reserved for Okinawan women — explains that appreciation is possible when there is an equal playing field, which we do not have. To navigate cultural appropriation, Maruyama believes we need to understand the pain it causes and how treating someone’s culture as a commodity can dehumanize them, and further justify their oppression.

Few are more familiar with this than Native Americans, whose appropriation and commercialization by non-natives is well documented. So entrenched was the problem that, in 1990, Congress passed the Indian Arts and Crafts Act, making it illegal to falsely advertise that Native American-inspired artwork was made by Native Americans when it was not. But certain symbols and images themselves, although sacred to indigenous people, are not protected by law and the act of someone from another background tattooing these images without understanding the history and traditions behind them is a long-standing issue.

Cyrus’ dream catcher is a case in point. The dream catcher tradition began with the Ojibwe tribe who suspended the woven willow hoops on cradles as a form of armor and protection for the child. The act of creating the dream catcher is sacred and an important traditional facet for the Ojibwe people and many view the adoption of the image by non-natives as inappropriate. While celebrities are happy to display symbols like this on their bodies, critics point out that few of them do anything to highlight the inequalities faced by Indigenous communities.

Arianna Lauren, a Cowichan tattoo artist based in Albuquerque known for her intricate hand-poked tattoos, explains that just because someone appreciates the culture doesn’t mean it is appropriate or respectful. She says she wouldn’t, for example, tattoo a dream catcher because she is not a member of the Ojibwe tribe. She believes that seeking out and talking to members of the tribe or culture from which the design or symbol originates is a good starting point when researching a new tattoo. It’s simply a matter of respect for artists who are approached to create a design from a culture they are not connected with to point the client to an artist from that community instead of profiting from it themselves.

Unfortunately, the risk of causing offense or disrespect to others is not always a deterrent. In fact, many thrive on it and offend as much as possible. Perhaps though, the threat of legal action will give pause for concern. While it’s unlikely anyone will land in legal difficulty in the U.S., many reports have emerged from Sri Lanka in recent years about the arrest, deportation, and even imprisonment of tourists who are perceived to be insulting Buddhist traditions. Buddhism is accorded the “foremost place” in Sri Lanka’s constitution and about 70% of the island’s 21 million people are Buddhist. Displaying tattoos of Buddha is considered extremely disrespectful and tourists being detained and subsequently deported for their ink is not uncommon. Although there are no confirmed reports of anyone receiving prison sentences over their ink, back in 2012, three French tourists were given six-month suspended sentences for kissing a Buddha statue.

Research is key and helps ensure one remains respectful of cultures and artistic practices that aren’t their own and helps them avoid other unintended consequences, like those who discovered their Chinese symbol tattoos translate to “western idiot” or “ham sandwich.” Or worse, the design they failed to research denoted them as a member of a notorious street gang or inadvertently affiliated them with the Russian Mafia. Laser removal is always an option but it’s painful and expensive and won’t undo the hurt caused to communities whose cultures have been distorted and exploited.

Editor's Picks

Hublot – Etched In Time

Tattooists are leaving their indelible mark on the luxury watch industry.