Inked Mag Staff

July 31st, 2024

Copycat Tats

Recent lawsuits about tattoo ownership are raising legal and ethical questions, leaving artists and clients uncertain about rights and reproduction of their inked artwork.

Who owns your tattoo?

By Elaine Maguire O’Connor

When you get a tattoo, the last thing you think about is who owns it. Given it’s your skin and you’re paying for a service, you presume you own it and are free to do with it as you please. However, a recent spate of lawsuits has raised myriad legal and ethical questions concerning tattoo ownership, leaving both artists and clients uncertain about what they can — and can’t — do with the artwork.

Historically, the tattoo industry operated outside the law and was not subject to the same laws and regulations as other art forms, instead relying on social norms that developed over time. As tattoos entered the mainstream, interest in associated copyright issues arose, especially when tattoos were used in advertisements and other media outlets where the original artist was not compensated.

Jimmy Hayden says when he first discovered the video game NBA2K, he was surprised to see his artwork featured prominently, mainly because nobody consulted with him about its use in the video game. Several years earlier, Hayden inked basketball superstar LeBron James with his distinctive lion head chest piece, as well as tattoos on his legs, back, and arms. James was depicted — with permission — in the NBA-themed video game. When Take-Two Interactive, the company behind the NBA2K game, refused to pay Hayden a license fee, he filed a lawsuit against it, arguing that the reproduction of his inkwork on James constituted copyright infringement. Although not the game’s focal point, the tattoo was recreated meticulously and used the same intricate details Hayden designed.

If Hayden were a musician or a graphic artist through any other medium, the creators of the video game would have been legally required to get his permission and obtain a license to use his artwork. He created the design and spent many hours affixing it to James’ body. And while he was aware that James would be filmed while playing basketball and perhaps featured in NBA promotional materials, he did not foresee the tattoo’s recreation in a video game.

In 2007, when much of the artwork was created, it wasn’t even on Hayden’s radar — the technology to recreate such detailed reproductions didn’t exist. It’s a valid argument, but while art creations are generally protected by copyright law, things get a little more complicated when the art in question is fixed to another human being.

Usually, copyright owners have the power to control the art, including augmenting or destroying it. Clearly, if this power extended to tattoos, we’d have some serious human rights issues at play. It seems unlikely any judge would force a client to receive laser treatments because the original artist or copyright owner wanted the tattoo destroyed, or conversely deny the client the right to remove or augment the tattoo should they choose. It is generally understood that, although the artist owns the copyright, an implied license exists for the client, which allows them to display the tattoo without prior permission from the artist.

Samantha Robles, the popular New York-based tattoo artist known as Cake, says that a number of her clients, many of whom are in the public eye, have asked her to sign release forms, making it clear that she will not sue if the artwork appears in a movie or music video. Cake explains that she is happy to sign these and doesn’t object to her work being featured in another medium.

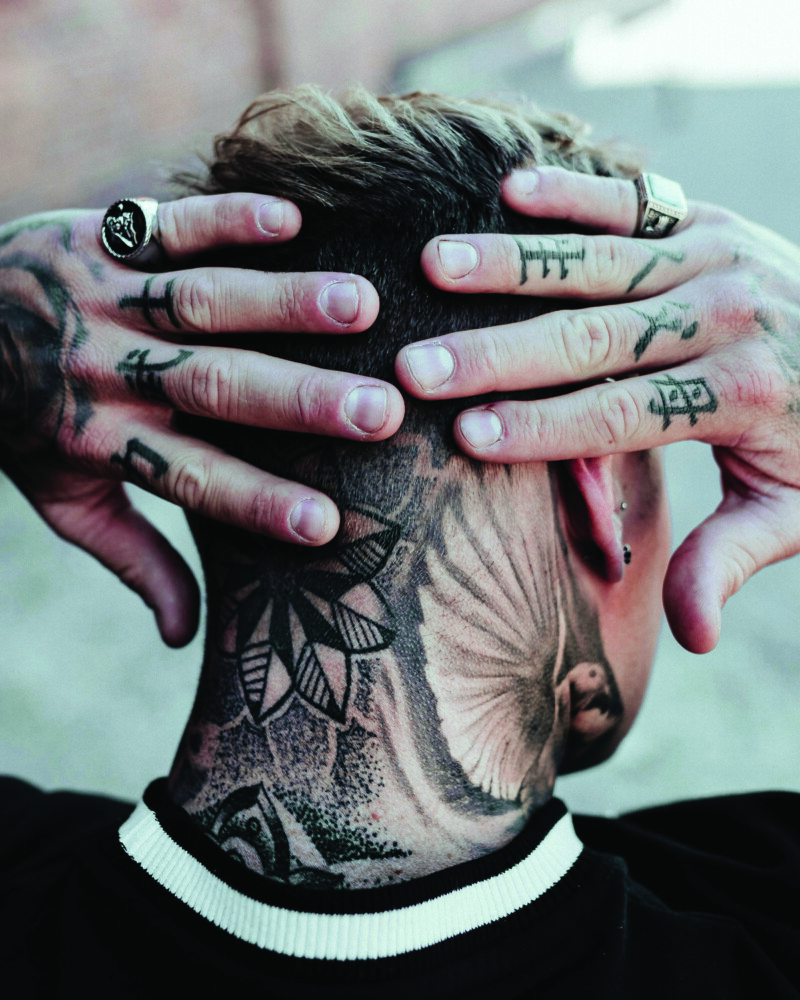

This might change, however, if she discovers her work as the focus of a commercial endeavor, like when S .Victor Whitmill’s design was used as a major plot point in “The Hangover Part II.” Whitmill, who was the artist responsible for Mike Tyson’s distinctive facial tribal design, sued Warner Bros. over the similar-looking facial art on Ed Helms’ character in the movie, seeking an injunction to stop the release of the movie. Warner Bros. was unwilling to risk box office profits while the courts debated the merits of tattoo copyright, so it was settled out of court. Like Cake, other artists are generally more sympathetic to leveraging copyright law if it involves the unauthorized use of designs where a large corporation is profiting from an independent artist’s work.

This went to the heart of Hayden’s lawsuit. Take-Two Interactive reportedly took in billions in revenue, yet Hayden received nothing, despite his artwork featuring prominently in one of company’s best-selling games. Other large corporations, including Nike, Hayden explains, previously sought him out and paid him to recreate the tattoos he designed, including the limited-edition sneakers, Nike Air Max LeBron 7. Take-Two, however, did not seek a license or ask to collaborate with Hayden in recreating the work for NBA2K. In April, an Ohio jury ruled in favor of Take-Two, who argued that the inclusion of the tattoos constituted fair use as they were only used to reproduce the likeness of LeBron James.

Artist Catherine Alexander who inked WWE wrestling star Randy Orton was of a similar view to Hayden when she sued Take-Two over the unauthorized reproduction of Orton’s tattoos without her permission in the WWE 2K video games. Unlike Hayden, the jury in Alexander’s case found in her favor. It awarded her damages, agreeing with her argument that she did not grant Orton an implied license to copy the works and did not give him the right to sublicense copying of the tattoos.

The differing results in Hayden and Alexander’s lawsuits create uncertainty, and it seems likely that formally drawn-up contracts or releases detailing who is entitled to control a tattoo’s reproduction in a commercial setting will become commonplace. Most tattoo studios already require customers to sign waivers relating to risks involving health and safety, so it’s not a huge jump to suggest copyright clauses will become standard before an artist agrees to ink a customer. Lawsuits are expensive and time consuming — working out these issues in advance may be the best way forward, however much they might jar with traditional industry practice.

The creeping copyright litigation we see encroaching on the tattoo industry and replacing the cultural norms that governed it for so long hasn’t solely involved corporates reproducing artists’ work without permission. In 2021, photographer Jeff Sedlik filed a lawsuit against Kat Von D over the use of his Miles Davis portrait as the basis for a tattoo she inked on a friend’s arm. The case had the potential to cause havoc in the tattoo industry, where it’s standard practice for artists to use photographs as references without asking for permission or a license beforehand.

Sedlik argued that he was the owner of the copyright, and Von D did not obtain a license. The court found in Von D’s favor on the basis that she made changes to the image’s appearance from the original work — specifically the shading and shaping, and therefore had a different meaning to the original. While a collective sigh of relief echoed throughout tattoo studios upon hearing the verdict, the lawsuit didn’t provide much clarity on what issues could arise going forward when tattooing artists’ photography. After the verdict, Von D said she may never create another tattoo because her heart was crushed by the ordeal, highlighting the emotional toll lawsuits can have on those involved.

One thing seems certain: unless written copyright provisions are included in waivers, the lawsuits will keep coming. And while copyright law may not quite map onto tattoos as it does other creative mediums, we can only hope that future court decisions will show sensitivity to the competing interests of both the artists and the client.

Looking for more content like this? Check our other articles here.

Editor's Picks

Bridging Classical Art and Modern Tattooing

Esteban Rodriguez brings the discipline of classical fine art to the living canvas of skin, creating hyper-realistic tattoos that merge technical mastery with emotional depth.

Show Your Ink Fashions Brings Custom Style to Tattoo Culture

Show Your Ink Fashions creates custom shirts designed to showcase your tattoos as wearable art, blending fashion with personal expression.

The Ultimate “Superman” Tattoo Roundup: Just in Time for Superman’s Return to Screens

With Superman’s big return to theaters, fans are revisiting some of the most iconic ink inspired by the Man of Steel.