Steeped in Traditions

Japanese tattoos are etched from customs and regulations.

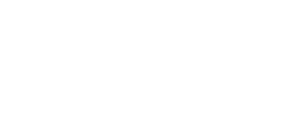

Inside an apartment in the Asakusa downtown Tokyo area, the ambiance is tense; the atmosphere is almost tangible. A male in his 50s, his muscles taught with pain, lies on tatami straw mats. The lower half of his body is covered in macabre images of a Buddhist hell, tortured bodies, and demonic figures. In contrast, his torso is embellished with celestial beings, heavenly deities, and divinities that bring protection and luck.

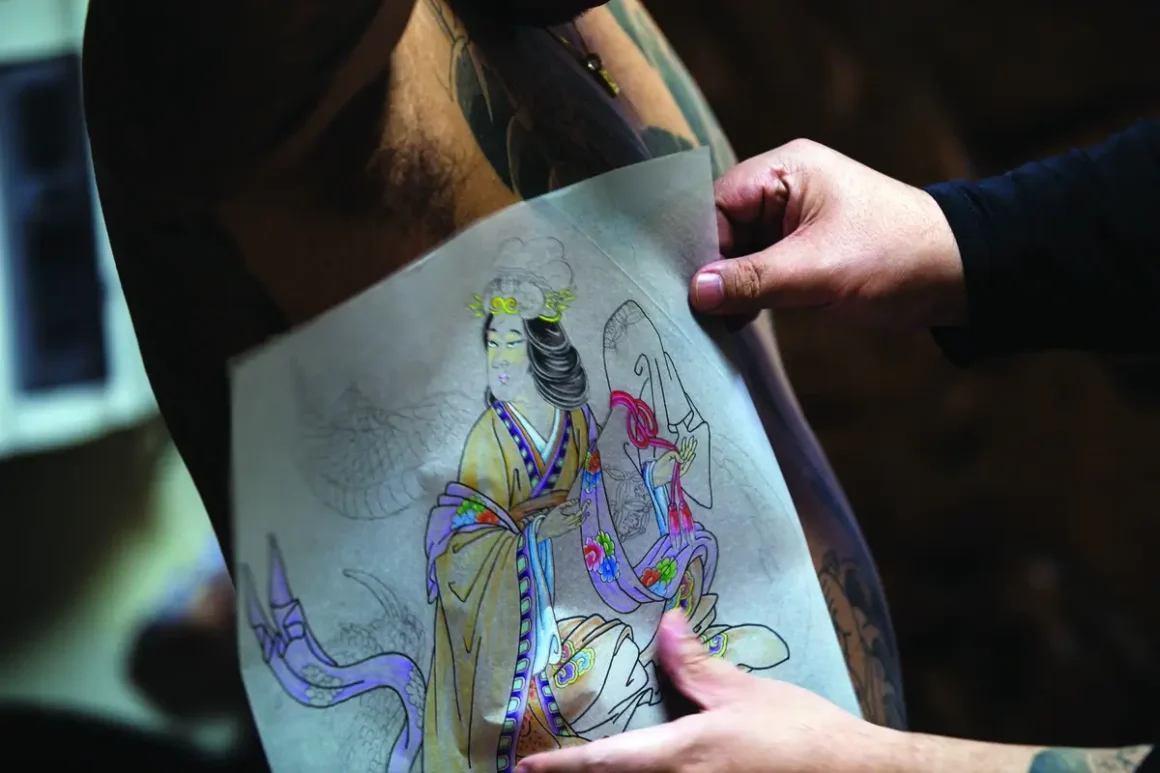

A Japanese tattoo artist, or “horishi,” Asakusa Horikazu manually inserts ink into the body with incredible dexterity and skill. The beauty of “tebori,” Japanese hand-poked tattoos, is incomparable, and he explains that Japanese ink is something that is “alive” and gradually improves with time. The black settles to produce a blueish patina that is the indelible quality of Japanese traditional tattoos.

Asakusa Horikazu is a “wabori” artist — Japanese style tattoos, as opposed to Western tattoos, or “yobori” — and is the son of the late Shodai Horikazu I. Asakusa Horikazu is a rare case of a horishi taking over a hereditary lineage, as most horishi usually ask for apprenticeships with teachers they are inspired by. He takes on a lineage with a clientele and identity manifested from living, working, and playing in the downtown Tokyo area. He follows in his father’s footsteps, and Horikazuwaka, or “Horikazu Junior” as he was then known until his father’s passing, became Asakusa Horikazu and took over his father’s legacy.

As this was essentially a family business, Asakusa Horikazu was consistently acquainted with his father’s work and knew he wanted to be a horishi as well, illustrating iconography such as dragons ever since he was a young boy. He explains that he started tattooing in primary school but “wasn’t taught anything and was just watching, learning and practicing on bananas and mandarin peels,” as well as his own body. “My first client was an elderly guy who was getting tattooed by my father. I was in third year primary school!” he says. “I was told I should not tattoo for free, so even back then he would give me 500 yen. Horikazu I would look with a magnifying lens to see if my tools were OK, and if not, he would let me use his. I did a lot of jobs like touch-ups.”

Asakusa Horikazu opened his first studio when he was 20 years old, where his clientele was mostly “local hooligans” who aspired to be like the folk who appear at traditional festivals. He then joined his father’s studio at age 25 and tattooed both his father’s clients and his own. While he tattoos many other Japanese horishi and traveling tattoo artists from abroad, his clients were and still are predominantly word of mouth, and he works with real-life relationships that are built on trust.

Unlike street shops of the West, horishi in Japan usually work from innocuous apartments with no signage outside. The world of tattoo shops only flourished with the popularity of small Western-style tattoos, called “one points” in Japan, and traditional Japanese tattooing still largely takes place in inconspicuous locations. For fans of Japanese tattoos, this discretion is one of the appeals of tattooing, and horishi see themselves more as artisans than artists.

Asakusa Horikazu says that the charm of Japanese tattooing is a ”hidden beauty.” “I don’t enter Japanese tattoo conventions. Japanese tattooing is a clandestine aesthetic. People show them off and walk around nowadays, but I would personally feel uneasy about it. It isn’t that cool if an old man is showing his tattoos and walking around, it would look like we were trying to scare someone, and it would be kind of crass.”

Indeed, much of this discretion is based on associations between the Japanese underworld and tattooing. Historically, tattoos were forcibly branded on criminals as a form of punishment, and from the postwar period until the 2010s, full body suits were mostly found on the yakuza, Japanese crime syndicates.

The long-standing illegality of tattooing in Japan is yet another factor contributing to tattooing’s underground image. It was subject to periodic prohibition bans since the Edo era, and in modern times, the practice was actually in a legal limbo, where tattooers working out of street shops were existing in what was often described as a “gray zone” until a few years ago.

Wabori Roots

No doubt any tourist to Tokyo has been to the Asakusa neighborhood, as it houses Tokyo’s oldest temple, the magnificent Sensoji Temple, built in 645. Japanese tattooing, as it is known today, established its roots in its downtown area. The region housed the commoner class that included artisans, woodblock artists, and merchants during the 1603-1868 Edo era.

During the thriving Edo era, an isolationist period of prolonged peace, tattoo culture in Japan flourished, alongside the culture of ukiyo-e woodblock prints and kabuki theatre. The motifs found in Japanese tattooing were and still are predominantly based on the popular woodblock prints of this era, and the two cultures grew hand in hand.

Today, aside from the utilitarian bathhouses that serve as community spaces for downtown denizens, tattooed people can be found at traditional festivals called matsuri, such as the massive Sanja Matsuri, Tokyo’s largest, rowdiest, and most energetic festival. Around 2 million attendees from across Japan attend, paying homage to the founders of Sensoji Temple.

In essence, Japanese festivals are important events for local communities and serve as performative ways to thank the gods and pay homage to the seasons. Matsuri festivals are exquisite aesthetic experiences with the primordial beat of the taiko drums resonating down the streets while ornate portable shrines called mikoshi are shouldered by spirited enthusiasts. Dozens of tattooed folk gather at this festival and participate wearing only a fundoshi loincloth. A large majority of the high-quality works on display at Sanja Matsuri are by Horikazu — both father and son — and their clients are seen dominating the streets of Asakusa during the time.

Asakusa Horikazu himself has been attending Sanja Festival since he was a child and manages a mikoshi shrine group. Most of his tattoo clients are interested in festivals and the two cultures go hand in hand. “We are helping keep matsuri culture alive and pass it on to the next generation,” he says. “Given that many of my clients go to Sanja Matsuri, before Sanja is the busiest time for me. They want touch-ups so they can show them off. My calendar is predicated on whether it is before Sanja or after Sanja; I think most people in Asakusa are like this.”

While popular culture is increasingly a digitally mediated experience, most evidently with the youth of Japan, the backstreets of downtown Tokyo are anything but technical, with analog interactions and relationships still of paramount importance.

Wabori has spread across the globe, but in Japan, with artisans like Asakusa Horikazu, it is a culture in context, inextricably linked to geography, culture, spirituality, and hierarchical relationships that are just as easily forged from bathhouse interactions to eating at local restaurants and jostling the shrines at a rowdy Shinto festival.