Inked Mag Staff

January 18th, 2019

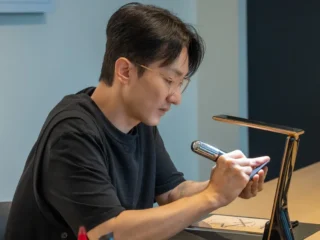

Exclusive: Shepard Fairey Makes His Tattoo Debut

Shepard Fairey Talks Futura (2000), the Obama Campaign and His Meaningful Tattoo

During the late ‘80s and all through the ‘90s he “bombed” countless cities across America. Being in New York City, it was hard not to pass a light pole, a doorway or an industrial alley that didn’t have Andre the Giant staring back at you…and New Yorkers loved it. At least, my friends and I did, although NYPD definitely did not. While in New York to talk about his new DAMAGE mobile APP, the 48-year-old Shepard Fairey visited our office, where he sat down to be photographed and talk about, well, his extraordinary life.

Let’s start at the beginning. I grew up in Charleston, South Carolina. My mom was head cheerleader. My dad was captain of the football team. It was a conservative upbringing. I went to the same private high school as Steven Colbert I wasn’t exposed to a lot of progressive art. I love to draw and paint from the time I was a little kid, but it wasn’t really until I got into skateboarding and punk rock that I started to see art that was non-traditional and that made a big impact on me.

When I got to the Rhode Island School of Design, that was a real melting pot of people. I started to be exposed to a lot of different perspectives — pop art and political art from people like Barbara Kruger and Robbie Conal. That’s when I started to connect the dots between artists like Raymond Pettibon, who did the work for Black Flag, Winston Smith who did the work for the Dead Kennedys and Jamie Reid, who did stuff for the Sex Pistols.

Tell us about Futura (2000)? I discovered Futura through the Clash. On the song overpowered by funk, he’s got a rap on it that talks about graffiti — “We threw down by night. They scrubbed it off by day.” Then I realized that he did the handwritten lyrics inside the Combat Rock album package and he did the “Radio Clash” single cover. He was a huge influence for me because, prior to that, I don’t think anyone other than Keith Haring had utilized so many platforms in a really effective way. And he’s also just a really cool guy.

Before the Andre the Giant, did you have a signature piece? Before I started the Andre the Giant as a sticker, there was nothing that I’d done that really stood out. I made a t-shirt and sticker design for a small company in Rhode Island called Jobless Anti-Work that incorporated Jack Nicholson from The Shining and the typewritten words “ALL WORK AND NO PLAY MAKE JACK A DULL BOY” and it became a huge hit for them.

So, I’ve got this viral thing happening on the street, within the culture that inspired me, skateboarding. And all of a sudden at 19 years-old, I begin thinking, I may be poor now, but feel like I could make this thing happen. And when I say this thing, I mean just being creative for a living. My ambitions were fairly modest. I just wanted to be able to survive within the culture that I loved. That’s all.

Please, tell us about the color red. I use red in most of my work for a few reasons. One, it’s very eye-catching. I mean, when you look at branding and advertising and propaganda, there’s a reason that red is a prominent color. Humans respond to it subconsciously and consciously. When they see red, they say to themselves, “You’re using red, what are you trying to say to me? I always wanted it to be provocative with my work. The other reason was as a very poor artist, I figured out how to rig the machines at Kinko’s so that I could get free copies from the red toner and black toner cartridges. So, I was going to design around red and black. But you know, when you look at the history of graphics in graffiti, the use of the, “Hello, my name is sticker” is almost always red and black. Barbara Kruger’s work is red and black and all the Russian constructivist stuff that I love is predominantly red and black. So, you know, there was a framework historically that led me to red and black as well. Not just the practical considerations of being broke and having access to Kinko’s.

You gain notoriety from the Andre piece, and then the Obama piece becomes huge. But do you feel like there’s a shift in notoriety in terms of who embraces the Andre piece

and who embraces the Obama piece?

My entire career, up until the ObamaHope poster, I had been basically working as an outsider. I’ve been critical of most of the dominant system, including President Bush. Obama was the first time I saw someone from the dominant hierarchy as worthy of endorsing and in a sincere way. That did shift some aspects of my fan base. A few people saw the connection between my criticism of Bush and my endorsement of Obama. A lot of the people said, “Oh, yeah, that’s a sellout move to embrace a mainstream politician. But I also was entering a phase of my life where, I had one daughter who’s two-and-a-half, and was about to have another daughter.

I thought I can throw pebbles from the sidelines or I can actually try to work with the inside-outside strategy. I felt that if you really want to make change, you’re going to have to engage with the dominant system at some point. And Obama could potentially be a subversive vehicle for a lot of the causes I believed in.

Do you feel like people knowing who you are now is a benefit or a curse? I worked for the first year of my campaign from ‘89 to ‘90 completely anonymous. I loved the freedom of going out and putting stickers and stencils up without anyone knowing who it was. I could step away and then cruise back and hear a conversation about the work. I did a lot of eavesdropping, which was really fascinating.

The anonymity can be an asset, but can also be a handicap. And the handicap is that the people who hate it and want to tear it down and say it’s bad for society, they’re very vocal. But the people that do it who don’t want to be outed, they keep quiet. And I thought, well, I’m outed now. So I’m going to try to be an articulate advocate for this art form. I’m going to use this as an opportunity.

I’ve been easier to find when people have wanted to find me and throw me in jail or threatened civil suits. But it also has meant that I’m thinking about how to stand behind what I do.

Tell us about the DAMAGE mobile APP. For me, doing the APP for my art show, Damage, which was the biggest non-museum show of my career, it was important for me to have people experience the show even if they couldn’t attend. The show was sort of a gallery warehouse space hybrid featuring a printing press, a newsstand, a billboard, a mural sculptures, and the APP allows people to experience that space virtually in a way that is incredibly visceral and tactile. It is something you can never achieve by scrolling through flat photos.

I want as many people as possible to experience the work. I want my work to be accessible. All these very labor-intensive projects that live in an installation for a short amount of time, now have that possibility to endure for people in app form.

Technology and the arts? Democratizing artists is important to me? I think art is a very, very powerful medium. It can be persuasive. It can be healing. It can be therapeutic for the creator and the audience. I think as human beings we respond to things that have been crafted with love and attention to detail. And I want to see that valued more in society.

I want a lot more people to feel that rather than just being impotent spectators, they can create. Everybody’s got an iPhone, which means they’ve got as much power as Metro Goldwyn Mayor had 70 years ago right in their pocket. It also levels the playing field and allows merit to rise to the top.

Tell us about your tattoo. I have one tattoo. It says diabetic in the Indian motorcycles script and the reason is, I’m a type one diabetic. I have been arrested 18 times and during three of those, I got very sick. My life was in danger from being in jail and not being given my insulin. For anyone who’s never been in jail, it’s barbaric in virtually every city, but New York City and Philadelphia are especially brutal. You don’t really register as a human being to them. In 2000, I was arrested in New York City and was in jail for three days – two of those days without any insulin. When I got out of jail, I was throwing up because my blood sugar was so high that my body was trying to expel anything in my system that could be turned into sugar. And if that goes on too long, your organs start shutting down.

The process of going into jail involves being fingerprinted, a mug shot and you’re checked for scars and tattoos. My wife made the suggestion to get a tattoo that says diabetic, so that the next time I go in, they have it on record that I’m a diabetic. So you can tell them, hey, I’m diabetic, I’ve got this tattoo. If they don’t believe you when you die, they can’t say they didn’t know. They can’t say you never told them. That’s a little bit of an insurance policy. So, it’s actually a really dark story why I have that tattoo. But, um, it’s pragmatic.

Editor's Picks

Bridging Classical Art and Modern Tattooing

Esteban Rodriguez brings the discipline of classical fine art to the living canvas of skin, creating hyper-realistic tattoos that merge technical mastery with emotional depth.

Show Your Ink Fashions Brings Custom Style to Tattoo Culture

Show Your Ink Fashions creates custom shirts designed to showcase your tattoos as wearable art, blending fashion with personal expression.

The Ultimate “Superman” Tattoo Roundup: Just in Time for Superman’s Return to Screens

With Superman’s big return to theaters, fans are revisiting some of the most iconic ink inspired by the Man of Steel.