Charlie Connell

February 3rd, 2023

Son of a Sinner

From rough-and-tumble roots to mainstream stardom, this genre-crossing musician is on a roll

Photos by Dylan Schattman

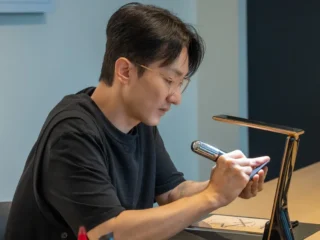

It’s a cold November morning in Hoffman Estates, Illinois, when Jelly Roll and I are finally able to connect for our interview. Just a few days prior, the rapper-singer was the toast of Nashville on the red carpet of the Country Music Awards, and before the afterglow dimmed he was back on the road, heading to the next show.

There is a hint of road weariness in his voice when he picks up the call, but after a quick cough it fades away. “We’re just out here putting boots to butts!” he bellows gregariously.

Jelly Roll’s presence is palpable even over the phone, and once you get him talking about music and the rocket-like trajectory of his career, you begin to share his zeal. He is grateful for the opportunity to be on tour, even when it results in a travel day from hell.

“I had two flights canceled on me at the last minute,” he says. “It was one of those perfect ‘story of my life’ moments where everything just went to shit. Then, the Hail Mary lob pass, and there’s a fucking jet sitting on the runway fully fueled up and ready to roll. We ended up making it, but it was close.”

Jelly Roll’s persona is a breath of fresh air. Where most celebrities would drag the airline that messed up their travel plans across Twitter, he recounts the happy miracle that got him to the show on time. Considering the path it’s taken him to get to these heights, it makes sense why he isn’t jaded. He understands these aren’t real problems.

Long before he was known as Jelly Roll, Jason Deford grew up in Antioch, Tennessee, a working-class community just south of Nashville.

“I’m from a family of super normal people,” he explains. “We were just super white trash, Southern fucks. My father was a meat salesman who booked bets and my mom was a bartender. One brother is a land surveyor, one’s in the meat distribution business, and my other brother works for the city or something. We’re those kind of people.”

Growing up, Jelly Roll’s house was filled with music. And as the youngest of four children, he was never given control of the radio, so he was at the mercy of his siblings’ respective musical tastes. Listening to him rattle off the many different influences he was introduced to at home is a little dizzying. “I had a brother who listened to hip-hop, a sister who listened to rock, a mama who listened to Motown and outlaw country, a dad who listened to classic country, jazz, singer-songwriters and soft listening.”

That hodgepodge embedded itself into his brain, setting the blueprint for the unique gumbo of hip-hop, country and rock that has made him a success. Jelly Roll’s musical influences played a less significant role in song structure and musical tones than they did in teaching him the emotional effects music can have.

“I was so fascinated with how music affected the people around me… how it would help my mother,” he says. “She’d be at the kitchen table smoking cigarettes and I’d watch as a load came off her shoulders when she put on a record.

“Every time I write a song, I’m thinking about how music made my mother feel and how I watched it make her feel,” he continues. “I think about how music made me feel at my darkest. There’s a quote that says, ‘Music is what feelings sound like.’ To me, that’s the importance of music.”

On his latest single, “she,” Jelly Roll went to some very dark places while writing a song he hopes will provide some light for people whose lives have been touched by addiction. It’s a subject close to his heart.

“For me, it’s not just about my personal struggles with that stuff, I also look at it from the perspective of my daughter’s mother, who is a recovering heroin addict,” he says. “My best friend struggles, his ex-wife and baby mother was friends with my child’s mother, and she overdosed and died in 2020. They were users together. You look at those kinds of circumstances and it’s past me, even.”

The CDC estimated that, in 2020, 11 people an hour died of a drug overdose in the United States. When Jelly Roll heard that statistic it blew him away. How was such a thing even possible? “Can you imagine the uproar if 11 dolphins an hour were dying?” he asks. The statistic stuck with him, but the callousness of our society hit him even harder.

“The idea we have where we look at people who overdosed and think, ‘You know, that person did that to themselves. That was their choice. That was suicide, practically,’” he says. “That’s not the right way to look at this problem. It’s not the right way to address an epidemic in America. It’s really sad. They think over 100,000 people will die this year from overdoses. I felt the holidays coming and thought we needed to put out some real music.”

People can see the statistics and hear about the opioid crisis on the nightly news, but unless they have had their lives directly affected it can be difficult to understand the reality. Often it takes a piece of art that appeals to a person’s soul for them to grasp the human toll addiction has taken. “she” does just that.

The chorus paints a particularly vivid picture:

She was the life of the party

She was the one everybody

Used to want to hang around

I bet they wonder where she is now

I wish I would have known

Before she was too far gone

I’m afraid to lose her now

She’s afraid of coming down

It’s the sort of real talk that is bound to move, and with any luck, broadly change some of the misinformed attitudes people have toward addiction. A song like “she” can have a profound resonance for someone who has experienced the horrors of the opioid crisis firsthand. It’s the kind of tune people will listen to when they’re at their lowest, specifically because it lets them know that they aren’t alone in their feelings.

A lot of Jelly Roll’s songs have this effect. Approaching darker topics with the level of honesty he does can be cathartic in the writing process, but it can also exact a toll.

“It’s difficult, sometimes, to carry the weight of those songs,” he explains. “Outside of the recording of it, the releasing of it, and the way it touches people. There’s a meme I saw that said, ‘We’d like to let y’all know, the state of West Virginia is no longer allowing people to play “Free Bird” or “Simple Man” at funeral homes. And we’re really close to canceling Jelly Roll, too.’ It was a joke page, but it hit me deep, that someone thought my music is played at so many funerals to make a joke of it.

“You know, that’s sometimes hard to wear,” he continues. “It breaks my heart, I’m such an empath where I’m sad for the family I don’t know that played my song. But it’s an incredible feeling to know my music helped somebody through a horrible time.”

Once you get beyond his hard-partying, always-laughing and self-deprecating shell, it’s clear Jelly Roll is an enormously empathetic soul. It’s even more remarkable when you consider where he came from. He spent a decent portion of his younger years getting into trouble with the law, and as such he spent some time incarcerated. Jail is the kind of place that often hardens a person, eliminating their compassion. Not for Jelly Roll.

Now that he has found himself in the position to help kids who are in similar circumstances to the ones he grew up in, he’s doing all that he can. And he’s doing it in a very familiar place—the same juvenile facility in downtown Nashville where he once spent some time.

“It’s crazy, it’s what you always dream of,” he says. “Giving back for me has never felt more personal. You walk into that juvenile center and, you know…”

Seeing where the juvenile system was underfunded, he’s working with Impact Youth Outreach to help establish an aftercare program where, among other things, they’re building a music studio in the facility. He’s also helping put together scholarships for local underprivileged high school students so they can get a chance to go to college.

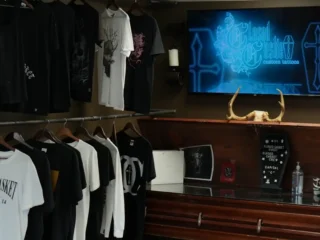

A strong sense of community is something that has been in Jelly Roll for years. It’s the way he was raised, and when you look at his arm you’ll see that it’s inked into his skin as well. The very first tattoo he got was a tribute in honor of a woman everyone in the neighborhood called Mama V.

“My first tattoo says ‘RIP Mama V’ on my right arm,” he says. “She wasn’t my real mama, she was like everybody’s mama in the neighborhood. She died of AIDS and I was 15 and got her name tattooed on me.”

As he filled up his body with an approach towards coverage he describes as “a bunch of sticky notes,” not all of his tattoos were as poignant as that first one. He’s a touring musician, after all, so he has a ton of sketchy tattoos gotten on a drunken whim. They may not be the most beautiful tattoos or packed with a ton of emotional meaning, but they still bring a smile to his face and they all have a story… even if not everybody remembers it.

“Did you ever have any sort of plan for building your tattoo collection?” I ask.

“Never, no way, not until way after the fact,” Jelly Roll laughs. “When it was way too late I started being like, ‘Oh, we should figure this out.’ I approached tattoos the totally wrong way. But at the end of the day, it is what it is and I’m not upset about how it worked out for me.”

Going with the flow has been a key part of his tattoo journey as well as his musical one. When he feels like writing a rap, he does. When he feels like strumming a country ballad, he does. It’s never about chasing trends or what’s hot on the radio—Jelly Roll’s music always comes from the heart.

“I’ve been writing songs for most of my life,” he says, “and I’m always evolving and writing differently as I do. I’m still learning new things every day. I’ll be learning for the rest of my life, I have that personality. The flip side of it is that as long as I’m eager to learn, I’ll be doing this shit.

“I’m only walking way from music when I just don’t fucking feel like doing it any more,” he continues. “I’ve got a feeling the business will beat me up before the songwriting. The road life, the 200 days away from the family shit. But I’ll probably always be writing songs. But the day I’m not enthusiastic about the bus call, I’ll really start reconsidering what I’m doing.”

Which brings us back to the beginning and Hoffman Estates. Jelly Roll had been put through the wringer trying to even get to a show the day before, missing flights and making it by the skin of his teeth, before having to load onto a bus to do it all again. He was in a Chicago suburb that has a lot more in common with a cornfield than with the actual city, freezing his ass off, and doing an interview with Inked. This is the exact type of situation where people mail it in and fake their way through it. Not Jelly Roll. He was turned up to 11 and eager to talk about anything and everything. Enthusiasm like that doesn’t just go away.

Jelly Roll is going to be making music and changing lives for a long time to come.

Editor's Picks

Royal & The Serpent

The hilarious and talented musician talks mental health, music, tattoos and more

A Cut Above

Celebrated barber Vic Blends can charge whatever he wants for a haircut, but all he really wants in exchange is a conversation and human connection

Building the Disney World of Hip-Hop

A conversation with Matt Zingler, co-founder of Rolling Loud, the largest hip-hop festival in the world